- April 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

As a little girl in 1940s Winter Park, Minnie Boyer Woodruff would head to work with her mom in the summer, cleaning Rollins College professors’ homes. Her mom would send her in to dust their plaques, certificates and degrees. When she was done with that, her mom would always tell her to go back and read them, and look at them very closely. Those accolades on the walls, she said, were what she wanted for her daughter.

“I want you to have an easier life than I had, and your ticket to an easier life is to go to college,” Woodruff remembers her mother saying.

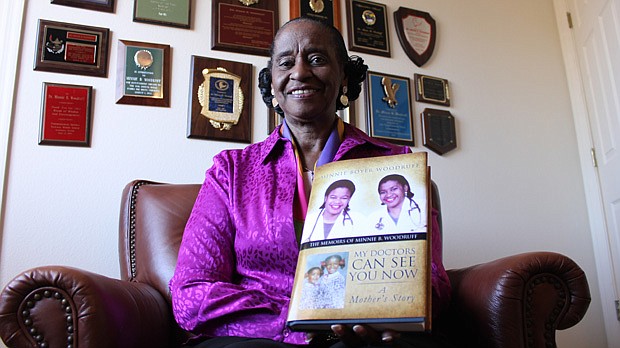

Now, Woodruff has her own degrees and awards in her own office. She’s got a doctorate degree, and was an elementary school principal for decades. That was no easy feat growing up a black child and woman in the ‘40s and ‘50s in the South. Impossible, some might say. But she did it, and so did her six brothers and sisters. They’ve got 19 degrees between them, five with doctorates. There was never a question of whether or not they would go to college, but where, Woodruff said.

“What is it that says ‘I won’t be denied,’ that inner calling,” she said. “We had a fire.”

To learn more about Minnie Boyer Woodruff and where to find her book, visit minnieboyerwoodruff.com

Woodruff never let that fire go out during any endeavor in her life, be it her marriage, career or raising her two daughters. She recently published a memoir, “My Doctors Can See You Now: A Mother’s Story,” reflecting on her life growing up in Winter Park and how she was raised with a strength of character and determination that she passed onto her own daughters. Both are now doctors, her oldest Dr. Edythe Woodruff Stewart is a surgeon, and the younger Dr. Conchita Woodruff-Johnson is an obstetrician gynecologist.

Woodruff said her memoir isn’t a rags to riches story, but a mother’s story. It’s a story about family, and raising children confident enough to take the road less traveled — a tradition, it seems, in Woodruff’s family. It wasn’t easy for either of the sisters to be black women entering the medical field, but they persevered. And their mother never questioned that they could do it; it was just in the genes to never give up.

“I could do and be anything I wanted to,” Stewart said of her upbringing. “There were never any boundaries put up.”

The sisters’ success, Johnson said, all started with their grandparents.

“Their ambition and their drive and their determination to make their lives better trickled down through the generations,” she said.

Both daughters hope to share that same philosophy with their own children, along with some of their mom’s other rules for raising children: sharing new experiences, valuing education, spending quality time with each child and letting them be themselves and try new things. And of course, family comes first, which was vitally important to their grandparents.

Growing up in Winter Park

The Boyers didn’t have much, but they had each other. The family of 10, plus a dog, lived on the west side of Winter Park on Douglas Avenue in a three-room home. While there weren’t any black men or women who had gone to college living in the family’s town to look to for inspiration, the eight children had their parents to encourage them. Both were domestic workers with an elementary school education. Her mother was a confident, in charge woman and her father was an intellectual artist.

Woodruff says she got her wit from her mother, whom no one questioned – especially not her father – and her smarts from her father, who would write stories and poems and advise the men in town on politics. Religion, community and education were the top priorities in their home, which meant taking to heart and respecting every bit of information their teachers gave. And they did, every one of them graduating first or second in their classes at Hungerford High School.

“Poor kids don’t have things, but we have our minds,” Woodruff said.

One moment that Woodruff will never forget, and what stoked that fire inside her, was being invited to Rollins College with her Girl Scout troop when she was 11. They went in back doors, constantly supervised – at this point in the school’s history the only black people there were servants, Woodruff said. But that didn’t matter to her. Those stately buildings she’d gazed up at as an outsider, she was now surrounded by.

“Now I was inside,” she said. “I wanted to be a part of that.”

And she and her whole family made sure they were a part of it, against all obstacles.