- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

After 45 days, George Zimmerman has finally been arrested for the shooting death of Trayvon Martin. A lot of people are wondering what took so long. You know the story of the protests and outrage that erupted in Sanford and quickly spread to the rest of the country because of the police department’s failure to make an arrest. Because George Zimmerman was white (though half Hispanic) and Trayvon was black, charges of racism were leveled at the police and State Attorney’s Office.

I have been trying to sort out my feelings over the matter and wondered why I didn’t experience the same level of outrage over the slowness in making an arrest. I guess it was because I am friends with many police officers and know their commitment to seeing violent offenders jailed. I also know the state attorney for Seminole County and his passion for getting violence off the streets regardless of the color of the offender. I figured that there must be some catch with the evidence that prevented an early arrest, but that justice would finally prevail. That is because “the system” has basically worked for me over the years, and I trust it.

However I began to think about it from the African-American perspective and “the system” has not worked so well for them. Not so long ago, black Floridians were murdered without justice ever being exacted from the people who committed the crimes. And back before that “the system” systematically humiliated, beat, raped and enslaved African-Americans. That sort of memory doesn’t fade easily. Even if the legal system works pretty well toward racial equality now, its past failures are likely to stir up strong reactions like the ones we have seen over the past month and a half when something even seems to go wrong.

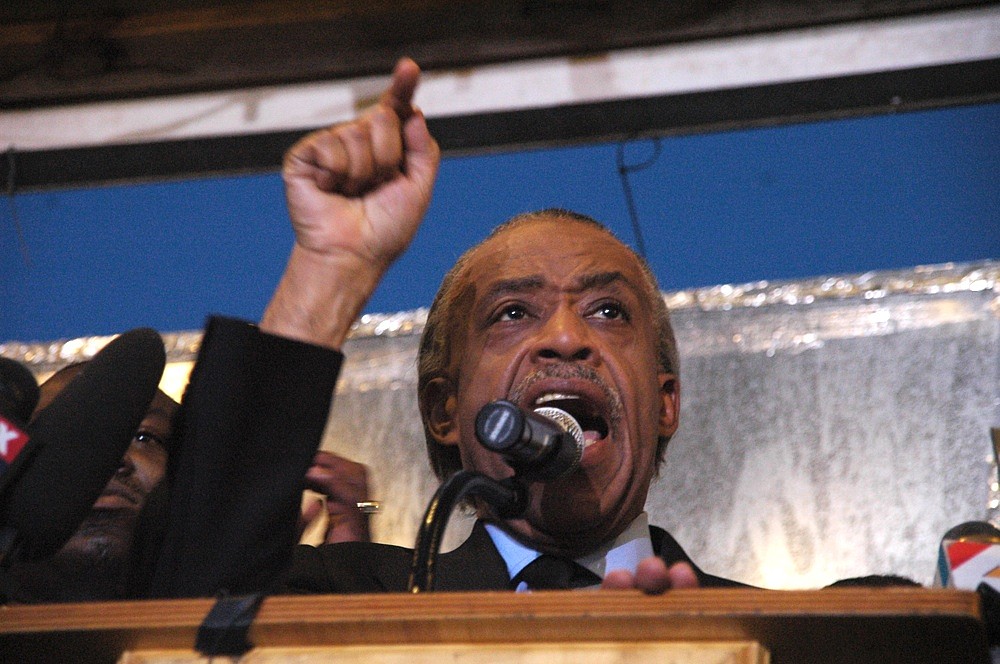

When Al Sharpton was here, he likened Sanford to Birmingham and Selma, Ala., during the ’60s. I don’t think he was right, but for many African-Americans the slow progress in Trayvon Martin’s case must have felt like Birmingham and Selma. Injustices that deep don’t go away overnight. They continue to hurt, and when touched can erupt into open wounds that create outrage.

Pain like this does not go away easily because injustice takes a long time to be satisfied. In his second inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln addressed this very issue in relation to the pain of the Civil War as being the outworking of injustice: “Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’" The sad thing is that the injustices continued to pile up even after the Civil War.

How does one work off that sort of injustice? You can’t. But the good news is that God can heal it. St. Paul said that the cross of Christ is able to break down walls of hostility between people (Ephesians 2:14). One of the bright spots of the past couple of months is how the pain of the Sanford situation has brought together black and white pastors across the community to pray together for the healing only Christ can bring.

For the healing to be real, though, there must be confession. My confession would be that I am only now beginning to catch a glimpse of how deep the pain runs in the hearts of my African-American brothers and sisters. I am so, so sorry, and I will make a conscious effort to walk alongside you and try to understand when you hurt. In another place, St. Paul wrote that when one part of the body aches the whole body feels it (1 Corinthians 12:26). If we’re not feeling it, are we really part of the body?

I also want to applaud the graciousness of African-American leaders who have continued to reach out to white leaders even when we didn’t understand. That effort to reach out will build a stronger community, which we will especially need as the legal system weighs the evidence in the Trayvon Martin case.

Rev. Jim Govatos, senior pastor of Aloma United Methodist Church in Winter Park, has served in full-time ministry for more than 30 years in places as diverse as Australia, Michigan (brrr!), and Florida. Before moving to Winter Park a little less than two years ago, he served as the senior pastor of Indian River City United Methodist Church in Titusville. A former atheist, Jim is passionate about helping people understand and experience a living faith in Jesus Christ.