- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Accidentally finding a landmine could be an explosive, even deadly discovery.

Accidentally discovering a way of finding landmines, however, as Ashley Cannaday found out, can lead to three years of research and a patent-pending procedure with the potential to be used across the globe.

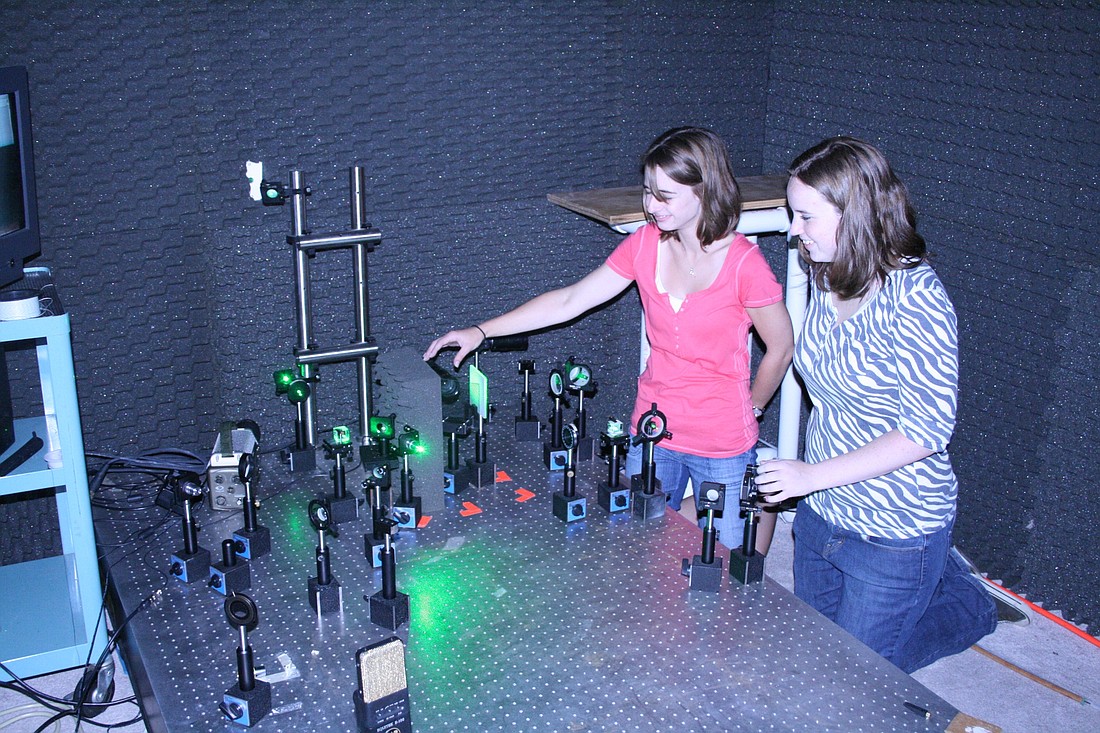

While the senior physics major and her Rollins College classmate fiddled around in the lab, trying to make a tuna can — the closest and safest alternative to using an actual land mine — vibrate, Cannaday stumbled upon a method for detecting an explosive mine’s vibrations in an unconventional way. Her tools: a single laser, a lens, camera, loud speaker, kiddy-pool, several pounds of sand and the tuna can.

“This whole thing was a complete accident,” she said. “We had this whole complicated setup with a beam going here and a beam going there, and they had to come together at exactly the right point, and one beam was going where it should and one was going up at the ceiling somewhere, but it still worked.”

That was nearly three years ago. Today Cannaday and Sarah Zietlow, a physics teacher at Hagerty High School, have developed and refined this new process of detecting buried landmines as part of the Rollins Student-Faculty Collaborative Scholarship Program, in partnership with Rollins professor Thomas Moore.

The trio had their findings published in the August edition of the Journal of the Optical Society of America.

“Essentially, the research started by just trying to find a better way for the detection of landmines because they currently don’t have one out there,” Zietlow said. “Currently the best way out there is some guy out in the field just prodding the ground with a stick.”

The procedure they developed revolutionized this process into one using acoustic dissizement coupling, or simply the use of sound vibrations to vibrate a buried object, causing the substance it is buried in to move. Once the process is patented, they hope to submit their findings to the Army for use as a safer, more practical way to detect landmines and prevent landmine-related deaths.

“It’s just directing a laser at the ground, expanding it so it covers the whole area you want to look at, and a camera. That’s the basic set up, it doesn’t get more complicated than that,” Cannaday said.

The vibrations are detected by the laser and recorded by the camera. The images are then processed by a computer that distinguishes whether the detected vibrations are that of a land mine.

“There are just a bunch of advantages of it over what they’re currently using,” Cannaday said. “You don’t have to be looking straight down at the object, which is good because if you don’t know where it’s at, you don’t know if you’re looking straight down at it or not. And this whole process to get a picture of where the mine is at takes a second, or even less than a second…and we’ll be able to tell you definitely there is one here, or definitely there is not.”

After an intensive eight-week research period over the summer, eight hours a day, five days a week, Zietlow said the team has a 100 percent success rate of detecting the presence of a mine.

Though the method of discovering this process was accidental, the teaming up of Cannaday, Zietlow and Moore was one year in the making. Zietlow had Moore as a professor when she studied at Rollins, and Cannaday was a student in Zietlow’s advanced placement high school physics class.

A grant by the National Science Foundation made their reunion possible. The grant allows Zietlow to work on the research at Rollins and in turn share the process and findings with her high school physics students.

“The kids really respond to stuff like this because they can actually see what they’re learning in action, which is really nice,” Zietlow said. “And as a teacher, the No. 1 question you get is, ‘Why are we doing this? What is this good for?’ So something like this is really useful to show the kids.”

Though Cannaday is scheduled to graduate in the spring, the future of her laser land mine detection method has just begun. Their true success, they say, will come once the procedure can be effectively used for landmine detection in-field.

Zietlow and Moore have high hopes that the partnership connection between Zietlow’s high school students and Rollins College will not end with Cannaday.

“I think after me, they’ve kind of developed a quota for incoming students,” Cannaday joked.