- April 24, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Lawrence A. Carastro has a simple goal in life: To protect and serve.

But after losing his first and only job as a police officer, and then years later getting arrested and thrown into federal prison for drug trafficking, that goal seemed far out of reach. During his prison stay and in the years that followed, Carastro traveled down a road to redemption that led him from a penitentiary to earning bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degrees from the Georgia Institute of Technology. Today, the Windermere resident proudly can say that he’s achieving his life’s goal through his work as an electrical engineer, but the road that led him to this point has been a bumpy one, to say the least.

“Terrible things happened in my life, and fabulous things have (too),” Carastro said. “I think I’ve come full circle. It’s not emptiness (anymore).”

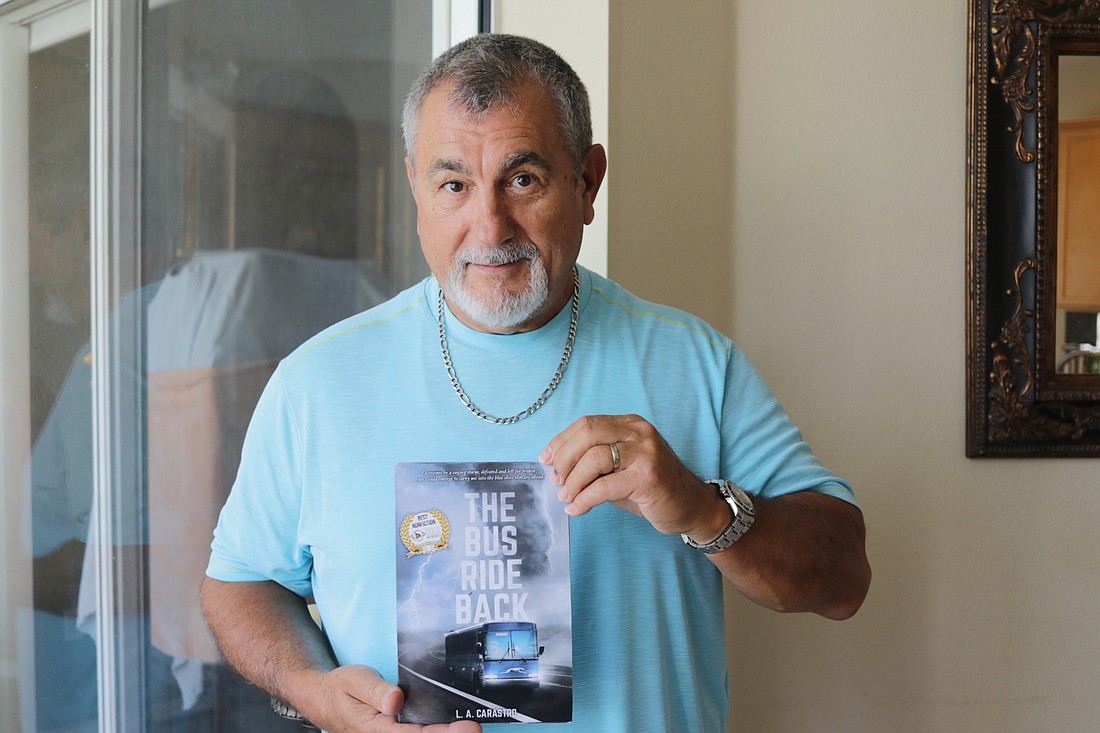

Carastro, 67, documents that road he’s traveled in his memoir called “The Bus Ride Back.” The title refers to the 20-hour bus trip Carastro took to Miami after he was released from prison. He doesn’t really consider himself a writer, but good storytelling is something he learned from his father. It’s that storytelling that earned his memoir first place for best nonfiction in the Indie Originals Book Competition, which is part of IndieCon 2019 in Melbourne.

Good cop with bad cops

Born and raised in Miami, Carastro worked for a South Florida police department for about five years while he was in his early 20s. The city he was in didn’t see a whole lot of crime compared to other nearby areas, but he was proud to be protecting and serving a community either way. He’s not a fan of guns, but he was good at using one when he was a cop.

“When I was a policeman, I shot a gun out of a guy’s hand,” Carastro said. “I never had a gun before. (I) haven’t really had one since (I was a cop). I’m not really a gun guy, but I could put a bullet anywhere I wanted. It was sort of scary.”

While working as a police officer, Carastro witnessed a darker side of law enforcement. There were a few rogue police officers who worked at that department at the time. Those officers would use an informant to set up crimes for them to investigate, he said.

“If there’s a moral there about (my) police (experience), it’s, ‘Don’t let policemen get bored,” Carastro said. “There wasn’t that much crime. … The detectives were bored, so they would get an informant, and they would work with him. They would have the informant set crimes up, and then they would be there to bust it.”

The turning point in Carastro’s law-enforcement career came when an informant was mistakenly killed during one of those crime setups. After that incident, he was used as a scapegoat for the misconduct of the rogue police officers and eventually was fired.

“The good guys and the bad guys were a little blurred at that point,” Carastro said. “I lost my passion. That’s what I wanted to do, and I was pretty good at it. After that, I got into the bar business.”

Carastro worked in the bar and clubbing industry for about 12 years. He had a successful career within the Miami club scene, and that work even led him to meet his wife, Sheri.

In 1986, during his career in the bar industry, he transported cocaine and marijuana from Miami to Philadelphia. Two years later, he was arrested for that crime and thrown into federal prison.

From penitentiary to doctorate degree

When Carastro was arrested, the charges he faced added up to more than a century of prison time. The judge, however, sentenced him to only 11 years, and a parole board reduced his sentence even further to a little more than two years. This was before the time of mandatory minimum sentences for drug-related crimes, Carastro said.

He spent eight months of his sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution, Otisville, in Upstate New York, and also spent time at the Federal Prison Camp at Eglin Air Force Base. It was at Eglin where Carastro’s road to redemption began.

“I learned some things when I was there (in Eglin),” Carastro said. “I met some really good people up there. (I met) some civilian employees that took an interest in me a little bit. They taught me electronics, and I sort of ran with that. This one guy said, ‘Go to school.’”

The electronics work he was introduced to in prison followed him when he got out. After serving his sentence, he went back to school to study electrical engineering and earned a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree and a doctorate in that field.

“I was 40 years old and I had to make a change, so I found my way back to school,” Carastro said. “I went to Miami-Dade Junior College for a couple of years and got my AA, and then I looked around for a five-year institution. … I looked at FIU and (University of) Miami, the University of Florida, FIT in Melbourne and Georgia Tech. They all accepted me, and Georgia Tech was my first choice.”

After finishing school, Carastro moved to the Orlando area in 2013. His law enforcement, bar work and drug trafficking days are far behind him, and he can proudly say that he once again is protecting and serving citizens through the job he works today.

“I’m developing circuitry for our Navy’s radar,” Carastro said. “There’s not a lot of us that do that, and I’m protecting and serving again on a much grander scale. … I’m whole again.”