- May 3, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

WINTER GARDEN — With no knowledge of the National Institute for Learning Development (NILD) or Reuven Feuerstein's Instrumental Enrichment Tactile program before Feb. 25, I was unsure what to expect when I walked into Foundation Academy that morning to examine part of a 45-hour, weeklong course for educators from across the country and world to support students with learning challenges.

Within a half-hour, they blindfolded me.

Todd Lambert, the cognitive educational therapist and Feuerstein Instrumental Enrichment tactile trainer from the International Renewal Institute of Chicago leading the session, used me as a test subject to demonstrate a unit of the enrichment program to the educators.

“The essence of this whole process is to be able to get to that thinking level,” said Valerie Lovegreen, speech language pathologist and cognitive specialist, “not math, science or an academic process, but to allow people to enhance the capacity to think and take in information efficiently by thinking it through and converting it to (another) form, being able to express themselves efficiently.”

Lambert mediated while I learned tactile information on a page like Braille paper, creating mental images to improve my thinking skills. It started with feeling lines to determine borders and structure of the page, which I had seen at the front of the room and briefly examined while Lambert was lecturing.

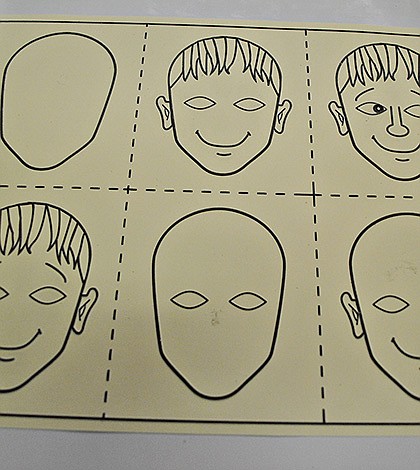

“This instrument is called ‘Facial Expressions,’ so everything we’re dealing with now is…faces,” Lambert said. “Now, I’m going to teach you…a strategy for exploration, called the tactile zoom. It’s a lot like that camera…you can zoom out to get a wide perspective, or you can zoom in to get that narrow perspective.”

Lambert had me use my palm and fingers, not to scan for details but to get an idea of each of the six boxes I had seen earlier on the sheet and tactually identified, creating a system of reference. Unlike visual stimulation, which is simultaneous, tactile stimulation can be successive. It starts by building a whole and then analyzing details.

The student in me wanted to race through what I already knew — the page had six boxes, each with a face of a differing number of details, like a “How to Draw Comics” tutorial — to finish faster, but Lambert’s steady, soothing instructions enabled me to relax and answer prompts one-by-one.

He moved my hand from the top-left box — a blank oval representing the start of a head — to the top-center box, which had more features, and I told him there was a lot more when he asked whether it was similar.

“That’s OK — we don’t even need to worry about that ‘lot more’ yet,” Lambert said. “We just want to know, basically — this is our wide lens — is it kind of like the first box?”

He then moved my hand to the other four boxes and asked whether something similar was there — yes. He summed what I had learned at a macro level before getting to details.

It was not a race or about finishing but learning techniques I could apply for learning in my life. I mentioned I had been diagnosed with ADD and taking medication based on extensive observation and psychiatry for many years.

“Welcome to my world,” Lambert said. “I also have ADD. I took medication for a long time, but this program allowed me to build the strategies I needed to stop taking the medication and to be able to deal with my ADD (and distractions) through different sensory channels and build the strategies I needed to be…that kind of learner I wanted to be.”

For instance, based on what I had seen, I knew the ovals I was feeling represented heads.

“That’s what our learners are learning right away: Seeing isn’t just with our eyes,” Lambert said. “We have these little eyeballs in our hands and fingers, and that’s what I’m teaching you to use.”

I felt the faces and used comparisons, memory and elimination to determine their order, from blank face to all features. As I went, Lambert put magnets on the boxes I had ordered, as if crossing them off a list.

“In ADD, we get lost in that detail,” he said. “We have trouble deciding what’s relevant and what’s not. But here in tactile, you very quickly made a decision that lessens your cognitive load and helps you to stay focused.”

As I continued, Lambert said I was excelling, and he used that to teach proper confidence mediation as students succeed or fail.

“As a mediator, you want to jump in there, but you can’t — you’ve got to let him go,” Lambert said. “It’s so easy to over-mediate in these instances, but he’s doing so well, I’m going to wait until he’s made maybe some sort of error he can’t overcome before I say something, or…until he finishes a certain strategy and then give him some feedback on how it could be more efficient…or until I see him become frustrated. Emotion messes up our cognition. We teach them to become aware of that emotion, and then we mediate a strategy to move through that emotion, so we don’t block and so we continue to think in that clear and efficient way.”

Each person thinks and learns differently, so each might approach tasks differently, he said. Lambert suggested superordination — comparative focus on one trait, not an image of a whole face. My task was determining order by faces’ number of features.

It reminded me of facial tests for my psychiatrist, but those involve matching faces by features seen, not tactile differentiation.

“Originally, this program was intended for blind and visually impaired learners,” Lambert said. “But we’ve discovered that, for people with ADD, this helps us learn how to filter out those distractions that come with vision, so that we can build better mental representations…to work on the world around us.”

HELPING LEARNERS

Lambert then indicated how I had hyper-focused on his voice and the page, a strategy this type of learning can build for him and many learners who struggle to hyper-focus.

Other beneficiaries of this program include the dyslexic, elderly, impulsive, those with autism and with brain injuries or PTSD, and people struggling to organize, read, verbalize thoughts or integrate senses, Lambert said. For all, it changes and fixes neurons in the brain and how they work — more efficiently.

“It’s about stimulating their minds in ways they aren’t used to, because this is a multi-sensory approach to gathering information, elaborating and communicating responses,” Lambert said.

When students lose focus, Lambert applies these principles to sound, causing disrupted students to focus on an abnormal sound, such as an animal noisemaker, drawing their attention back to the educator.

Everyday and even gifted learners can benefit from this tool.

“When I was in elementary school, my teachers always said I was such a gifted learner,” Lambert said. “I never felt like a gifted learner. Once we got to higher grades, when I had to do homework and stay organized, my ADD took over, and I wasn’t this gifted child anymore, but everyone still called me that, and that gap just grew. I would just see something and know something, but only in certain domains — my knowledge didn’t extend into other domains.”

Some parents think gifted children need less direction, which Lambert thinks is terrible.

“While I was often called a gifted child, I didn’t receive what I really needed,” he said. “That didn’t become apparent until I really needed it, in high school and college. I didn’t go back for higher education until I was 38. I actually got kicked out for academic non-compliance — I couldn’t finish my assignments. This program enabled me…to go back and get my master’s degree.”

Like Lambert, adults always said I was a gifted learner. I took gifted classes through elementary school, whizzing through math. But I recall two glaring times in first grade I lost focus and suffered academically and emotionally: Once, I spaced out for worksheet instructions until I noticed classmates rising around the room to submit theirs, pressuring myself to finish in time. Another time, I could not focus on object details to recall minutes later for a drawing, leading to tears.

Lambert and I wish we had this tool while we were students, because it could have changed our lives.

“Not to say that I’m not in a good place now — I’m exactly where I need to be,” Lambert said, “but it could’ve been nice, if you think about those kids who fall through the cracks, who may not have fallen through the cracks with this kind of work.”

Contact Zak Kerr at [email protected].