- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Joe Fana was one of millions of people to receive a surprise phone call on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

“My wife called me on my work phone, which she never did, and told me a plane just hit the World Trade Center,” he said.

The news would have a unique impact on his job as a fourth-grade teacher.

“We had to carry a calmness in the midst of tragedy,” Fana said of the mindset at his school, The First Academy.

“We did have a little bit of a discussion about what happened and tried to focus on the heroes who helped. It was that way for the next month or so, when kids had questions we would tactfully answer with facts but without fear.”

— Jennifer Douglas

Later that morning, Jennifer Douglas had the same feeling as she returned to her third-grade class at Rock Springs Elementary after learning of the attacks.

“There was a messenger from the office who came around and said, ‘Don’t say anything. Parents are coming to check (the students) out. We’re going to let them handle this,’” Douglas said.

The tragedies of that day affected the rest of the school year and beyond. But the desire for discussion was the same in every classroom.

“There was so much uncertainty the first day,” Fana said. “On the second day, as kids were coming back, we at the school were wanting to have that dialog: ‘The important thing is we want you to express how you’re feeling.’”

Teaching at a Christian school meant Fana and the staff could use faith to reinforce their compassion and share a sense of strength.

“The idea of us coming together in prayer … that faith element of being united in Christ but also unified as a country,” he said. “That carried over despite the tragedy, with the message that we’re going to be unified.”

Douglas, who was teaching at a public school but now teaches at Foundation Academy, conveyed another message of hope and strength.

“The idea of us coming together in prayer … that faith element of being united in Christ but also unified as a country. That carried over despite the tragedy, with the message that we’re going to be unified.”

— Joe Fana

“We could not pray, but we had moments of silence,” she said. “We did have a little bit of a discussion about what happened and tried to focus on the heroes who helped. It was that way for the next month or so, when kids had questions we would tactfully answer with facts but without fear.”

The events of 9/11 have since become part of history, but they still can be topics of anxiety and fear that require attention and compassion from a new generation of educators and parents who may not remember, or had even been born on Sept. 11, 2001.

“You can talk about it at any age,” said Dr. Stacy Carmichael, of Winter Garden-based MindWorks Psychological Services. “If you’re talking to elementary-schoolers … you’re not going to get into the in-depth conversations you would have with older kids. But I see a lot of kids with anxiety disorders. … Once you get one worry stuck in your head, you worry about a lot of things.”

Age and learning disabilities notwithstanding, questions or concerns always should be met by honest and reassuring dialogue.

“Listen to what their worries are and normalize and validate,” Carmichael said. “‘Of course, it’s OK to be scared. It’s very normal. I was scared, too, when I watched it. I was worried that it might happen again, also.’ Talk about safety procedures, things that make you feel better. Hopefully, we can reassure them this won’t happen again.”

Regardless, educators say it is imperative that the attacks are not ignored.

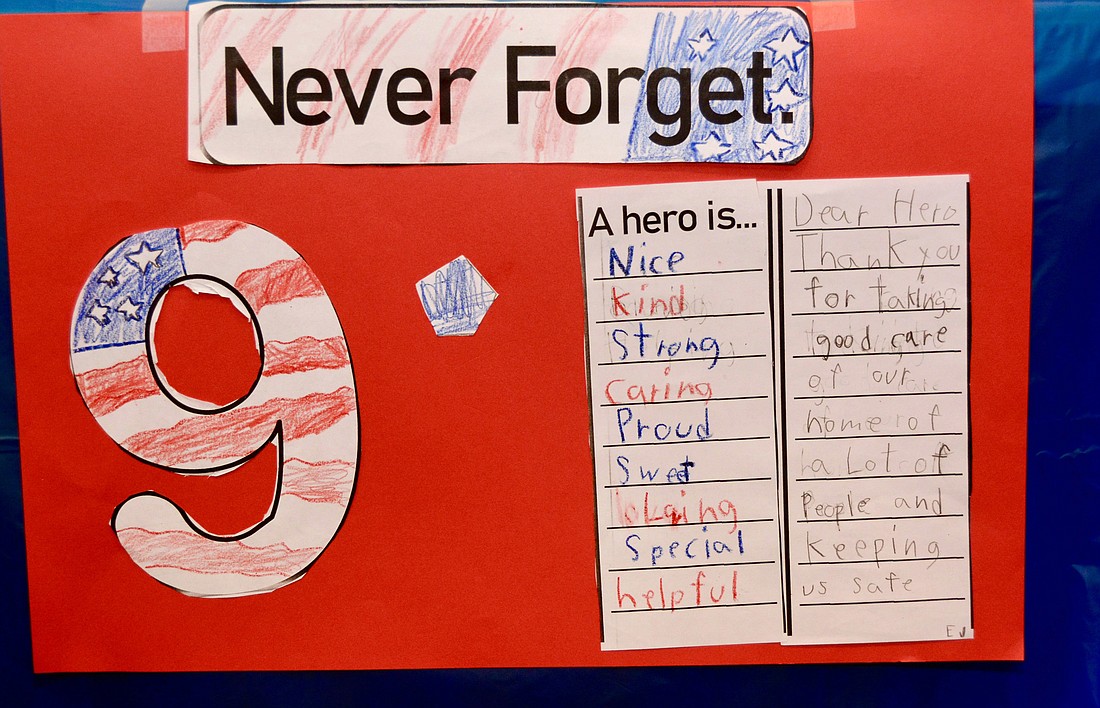

“It’s vital that we never let our kids forget — not only for the lives lost but the lives impacted,” Fana said. “It’s the idea of remembrance but also to make sure they understand, historically, what happened.”

For Douglas, the approach that worked on Sept. 12, 2001, is still valid.

“The heroes, police officers, soldiers the everyday person who stepped up — that’s what we put our focus on at the elementary level,” she said. “As a teacher, you want to broach it with facts, but you don’t want to instill fear.”