- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

It is likely that, even if you don’t play high school sports, you’ve heard the words “recruitment” and “commitment” in relation to student-athletes.

According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, out of nearly eight million students who play sports in high school, a little more than 480,000 will move on to play at the collegiate level. Of those, only 2% will receive some form of athletic scholarship to compete in college.

“I tell my kids, you’ve got to love your school,” said Brad Lord, Foundation Academy football operations and athletic collegiate placement director. “To get the sport, you’ve got to love your school, because you are going to spend the next four years of your life there. So don’t just pick it on, ‘They’re a great football team.’ You better love the school, feel at home with the coaching staff, (find out if) they have the resources, (what) tutoring they provide for athletes, all those things come into play.”

THE PROCESS

The recruitment process begins as early as freshman year — or in some cases, even earlier.

The process can go both ways. Either college coaches get in touch with the student-athlete, or the high school coaches or athletic advisers start contacting college coaches.

“If I see there’s a kid interested in playing at the next level, first of all, I’ll meet with the parents and the student-athlete,” Lord said. “I’ll give them a candor and honest opinion of where I think they will land: Division I, FCS, Division II, Division III, NAIA. Then I’ll send a press release out of the athlete to the coaches.”

For college coaches, the recruitment process is a constant competition of securing the best talent for their respective programs. The earlier they start, the better chances they have at developing a competitive program.

“It locks (the player) up, and the other coaches stop recruiting that kid whenever they do decide to go there,” said Eric Lassiter, head coach of the Windermere High School baseball team. “There’s so much money involved, and it’s not for the kids, but these coaches are making a lot of money and their job requires them to win.”

Lassiter described the process as a waterfall or trickle-down effect. Despite not being able to sign the athletes at such a young age, schools start recruiting them with verbal commitments, because other schools are approaching the players earlier, too.

CHANGING MINDS

However, those early verbal commitments — some coming as early as middle school — sometimes change. And sometimes, they never materialize at all.

“There’s just so many more things that can happen throughout the next three years if you commit as a freshman compared to if you do it when you’re a junior,” Lassiter said. “But it’s up to the college coaches who are doing these commitments early to be able to evaluate a kid and see what they think he’s going to be in three years. So it’s kind of on them to do that.”

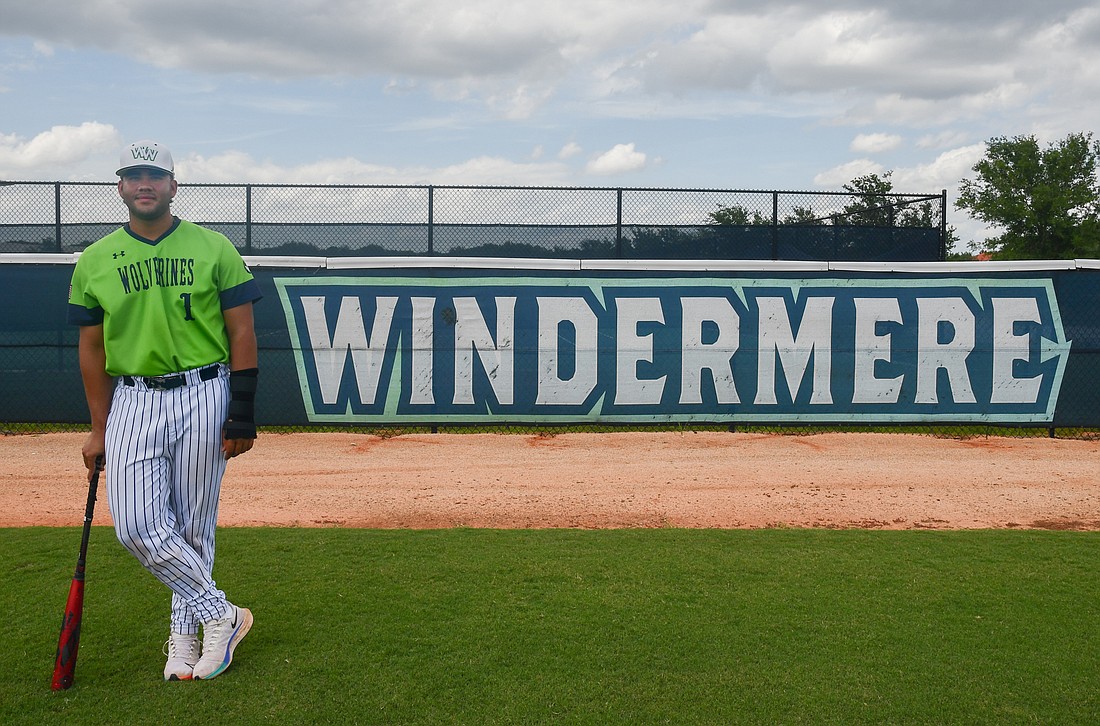

For Windermere High School senior Gustavo Mendez, the recruitment process started during his sophomore year, when he started to hear from different colleges. During October of his senior year, he received a verbal offer from Grambling State University in Louisiana to play baseball at the Division I collegiate level. Mendez is a catcher for the Wolverines.

“I waited until December, and that’s when I took the decision to do a verbal agreement with them,” he said.

For Mendez, the verbal agreement never made it to paper. During the 2022 season, he decided to retract his verbal commitment and accept an offer from Chipola College, a junior college.

“Grambling is a good program,” he added. “But I think Chipola College is a better opportunity for me to develop as an athlete and as a person, too.”

Mendez’s long-term goal is to enter the baseball MLB draft. If he had signed with Grambling State, he would have had to wait until his third year of college to be able to enter the draft. Chipola only offers two years of college education, so he will be eligible to enter the draft at the end of his sophomore year.

“I may go to a Division I after,” Mendez said. “Or maybe if I get a good offer right out of junior college, I’ll probably take it.”

Foundation quarterback Sabby Meassick — an eighth-grader — received a verbal scholarship to the University of Florida in October 2021. When he received the offer, he had not yet started a single game for the Lions.

Fast-forward seven months, and Florida has a new football coach in Billy Napier.

And although the change has Gator fans excited for the upcoming season, it throws offers such as Meassick’s into uncertainty.

“I don’t know if this new coaching staff is going to hold on to the offer,” Lord said. “They are probably not looking at eighth-graders right now, because Florida needs to get old quick.”

Enter, the transfer portal.

THE TRANSFER PORTAL

The transfer portal is a database of every player looking to transfer from his or her current school. This portal is available for every sport at the collegiate level. To enter, a student-athlete must notify his or her school’s compliance department. The student is required to tell his or her coach before he or she is entered, but once they go to compliance, they have 48 hours to be entered into the portal. Once in, schools can begin contacting the student. The portal allows students to transfer schools only once during their collegiate careers.

For Florida, that may be the best way to assemble the Gators of the future. And it may leave Meassick on the outside looking in.

“That’s how you get old quick, you go through the transfer portal,” Lord said. “You get juniors and seniors (who) are eligible for the transfer portal who fit your program, and you don’t have to take a risk on a high school kid.”

Foundation Academy alumni Cory Rahman and Evan Thomson both utilized the transfer portal. Rahman initially attended Southeastern University (NAIA) but later decided to enter the portal and transferred to Tennessee State University to play at the FCS level. Thompson initially committed to Florida Tech to play at the Division II level, but because the school shut the football program during COVID-19, he decided to transfer to Kennesaw State University.

The transfer portal can bring some negative consequences to the world of high school sports. Lord said about four years ago, universities had between 25 to 30 spots to fill with high-schoolers. Now, they may have only five or six sports available.

“It makes it hard, but at the same time, a coach can get up and leave whenever he wants for the next big gig,” Lassiter said. “So, I think that to allow them to do it one time if they are not happy is good. I don’t think they should allow them any more than that.

“But it’s just going to be a fine line there,” he said. “Because everybody thinks if they don’t like their situation, they can just pack their stuff. I’m not sure that’s necessarily what we want to be teaching young people — that if you are not having success or you’re facing some adversity you just pack up and leave and run to the next big thing. I don’t think that’s going to help you out in real life. … You got to figure it out in real life.”

MATTERS OF MONEY

Since last year, college athletes are able to receive a form of compensation from playing at the collegiate level known as NIL deals.

This compensation is usually money earned by the student-athletes when their name, image or a reference of their persona is used for advertisement or social media shoutout by their university and sports team.

“It’s crazy, because now the kids aren’t just going to pick their school based on the sport,” Lord said. “They are going to pick it on how much money they can make.”

For Lassiter, NIL deals can help student athletes get through college without having many financial hardships lurking on the back of their heads.

“Say you don’t have a lot of money — that’s paying for your school,” he said. “When you are giving these NIL deals, it might help … ensure (students) are going to get a college diploma. If baseball doesn’t work out, then they have that diploma rather than jumping ship early, because they are not making money, and their parents are struggling to make sure the ends meet. This kind of fills that gap. I think for baseball, it could help students stay in school longer.”