- July 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Rob Spolsino had just come home from mountain biking on a Sunday afternoon this past spring when he felt a little odd. Maybe it was a cold, he thought, dousing himself under a cold shower before going to sleep. Less than two days later, the life the young, athletic Rollins grad knew disappeared beyond a hospital door. The emergency surgery was just the start.

Two days before his friend rushed him to Winter Park Memorial Hospital in a panic, Rob was “Big, Big Rob,” as his friends and fraternity brothers would call him. Six feet tall and 185 pounds of muscle, he was the guy who broke a Rollins rowing record that hadn’t been touched in 15 years. He was the mentally gritty adventurer who would sweat out a cold on a running trail. Nothing could stop Rob.

So when Rob slept through that night and all of the next day, his close friend Matt Killian thought that cold may be the flu instead.

“I'll run tomorrow and sweat it off,” Rob said.

By the next day, running wasn’t going to happen. His body temperature soared to 103 degrees, yet his skin froze. When Rob called Killian asking for a ride to a doctor, he left work immediately.

“If you know Rob, the fact that he's asking to go to the doctor is already a red flag,” Killian said.

They drove aimlessly at first. Rob had asked to go to a doctor, but Killian saw something far worse. Rob, the well-built 24-year-old, was visibly shaking now. Killian turned the car toward the hospital instead.

In the small emergency room of Winter Park Memorial Hospital, Rob's vital signs were anything but normal. His blood pressure had dropped to a dangerous low. Ashen gray, he was barely conscious. Within just a few hours, he had seen six different doctors, who transferred him to the ICU before they realized how dire his situation was.

Rob was rushed to Florida Hospital, where they realized he needed surgery immediately.

Stay close, the doctors told Rob’s parents, Bob and Nancy. They'd better not leave the hospital, they said, the grim implication clear.

The diagnosis came in as sepsis — a potentially life-threatening condition caused by a bacterial infection reaching the bloodstream. Doctors found an abscess in his psoas muscle, a large back muscle running from the spine to the femur and accessed only through the abdomen.

“We're not certain how that [abscess] was caused or where it was originated,” said Dr. Timothy Childers, Rob's surgeon at the Florida Hospital. According to Childers, Rob's condition resulted in multi-system organ failure: his kidneys, heart and lungs stopped working as doctors worked to keep him alive.

Sepsis kills between 28 and 50 percent of all patients with the condition, according to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Some would say that when he came in through the door, Rob may have only had a 10 to 15 percent survival rate, Childers said.

But Rob was used to overcoming odds.

A record-breaking history

His life revolves around fitness — training is his first priority. Rob and Killian often trained together at the gym, or biked through trails in Chuluota. His solution to any physical problem would be to go for a run or a bike ride. He and his friends were once at a bike race in hilly Clermont, and — at the shock of his friends — he raced on a simple fixed-gear bike. It was the only one he had. On that punishing, notoriously hilly racecourse, with one gear instead of the other bikes’ 21, he finished with the top group at the finish line.

Pedaling downhill on a fixed-gear bike is especially dangerous, said Mitch Verboncoeur, Rob's friend and former crew teammate who was also at the race. He was shocked to see Rob determinedly push through.

The Rollins psychology graduate rowed on the crew team in college, taking away first-place medals and tirelessly training for hours at Winter Park's U.T. Bradley Boathouse, even after graduating. Friends would try to persuade him to go to parties, but he isn't a fan of big crowds — he prefers one-on-one interactions. For an introvert like Rob, the boathouse is a personal gym — quiet and emptier. It's rustic but spirited, with wooden paneled walls and a bright lake view. Everyone knew each other there, and with Wi-Fi and a shower, he almost never had to leave.

At 6 feet tall, he’s still considered shorter than the average rowing champion, but the resilient athlete broke the crew team's erg test record in 2012. That test, on an electronic rowing machine that calculates speed, hadn't been broken since 1997.

“He's got this way to just do more and tell his mind to be quiet,” said Brandon Thompson, assistant coach for the Rollins crew team. Thompson remembered Rob's will power and his astute nutritional habits and staples — rotisserie chicken, egg whites and oats, which he would bring to a personal mini fridge he had stowed in the boathouse.

Rob said that part of striving to break the record was for his own goal setting, but he also wanted to show the team that it was attainable.

Losing it all

Emergency surgery was just the start of Rob's new life. Three months of hospitalization and five surgeries caused Rob to lose more than 40 pounds: he went from a lean 185 pounds to a gaunt 130 at his lowest point.

“He looked more like a machine than a human being,” his father Bob said.

For the past few months, instead of waking up at 4 a.m. to row or train like before, he would be woken up by nurses for lab tests. Instead of running a mile to burn off frustration, simply rolling to the side of the bed was a painful struggle. Weak, fighting his own body, he had to will himself to get better. But that usual gritty optimism was gone, Killian said. He’d seen it drain out of Rob in that bed.

Slowly pulling through as his septic blood returned to normal, he realized fitness, now seemingly a far off luxury, would have to be built back from scratch.

“In the beginning, they kept saying, 'He's young, he's strong, he's young, he's strong.' And then towards the end they just said 'He's young,' 'cause all his strength was gone,” Bob said.

Now two months out of the hospital, and with one surgery left, Rob is determined to gain it all back.

“Once this final surgery happens, I'm gonna get back on it,” Rob said. “Things are a lot easier to do when it's a challenge, something you have to overcome.”

Support from the community

Jamieson Thomas vividly remembers the day she first met Rob at the boathouse. It was a dark, cool September morning and pale blue-gray clouds gave way to shy, muted streams of light from the almost-sunrise. It's quiet, and every sound is amplified. She looked over to the crowd of college kids who were still not on the water, huddled together on the dock, and set out on the lake to row solo.

“We all just go about our own business for the most part,” Thomas said. Sometimes the college rowers would smile and acknowledge the master rowers, but it was different with Rob — he had a different presence, she said. She was halfway out on the water when his crew was about to set out, and Rob yelled, “Hold up the boat! There's a single on the water.”

“It was a moment of awareness and thoughtfulness,” Thomas said. “He is a thoughtful, kind, giving young man.”

She was shocked to see the bright-eyed, selfless youth unconscious when she first visited him in the hospital.

“He didn't look alive,” Thomas said, with tears in her eyes. She remembers the way his chest quietly rose and fell as she touched his hand, telling him things she hoped he would hear. “Sending you good energy. Hope you can feel it.”

About two weeks before he was released, Thomas remembers being with him when he took his first steps to walk again. He stood up, his face and neck thin and skeletal. He was able to walk halfway down the hall for the first time since being in the hospital.

“There's a reason it happened, and I always wonder why,” his mother Nancy said. An administrative manager at a parish in Naples, Nancy was kept from the hospital for weeks at a time because of work, but the community back home helped her cope with her son's illness. The people at the parish prayed and cooked for her often.

In the beginning, Nancy said she would break down constantly throughout the day, feeling as if this was a nightmare from which she would wake up at any moment, but a second wind took hold of her. “It will work out; I have no doubt,” she would tell herself in between the tears.

Friends and old classmates were always visiting Rob at the hospital and when he returned home.

“Rob was definitely there for me when I was low on sleep ... I was low on sleep on most days,” said Verboncoeur.

His calm, unassuming nature seems to be a common impression among people who know him. “He's not a guy that gets vocally angry, never heard him yell at anyone,” Verboncoeur said.

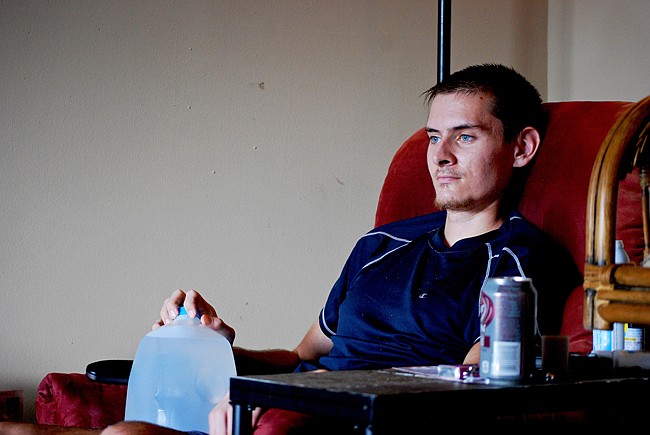

Even against the red leather recliner that mimics the position of a hospital bed, Rob's posture is solid, straight.

“I've realized it's a gift to be able to do those things; it's not just given,” Rob said, reflecting on fitness as the “constant” aspect of himself prior to the illness. “Not having that has forced me to re-evaluate things now.”

Things feel more meaningful and important to him after this foreign experience, and he hopes to take up a future career in coaching and study sports psychology.

Rob's piercing blue eyes give a glint of vigor that still surfaces, despite the blurry, surreal struggle of the past six months.

Slowly emerging from this unexpected challenge, he now has a new one; becoming “Big, Big Rob” again.