- April 16, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

The American Dream always has come at a price.

On Tuesday, Nov. 2, 1920 — Election Day — the members of Ocoee’s black community found out just how steep that price was.

On that day, the simple act of voting by prominent members of the disenfranchised black community sparked an outburst of racial violence that ended with an untold number of murders, the burning of homes and the exiling of a once-thriving community for decades.

Despite that moment — known now as the Ocoee Massacre — being the largest incident of voting-day violence in United States history, little is known about what actually took place. There are some known facts, but conjecture has weaved its way into a narrative that bleeds into realms of reality and fiction depending on whom you ask.

These stories, and the history of the moment, are now being reflected on by the city of Ocoee — which is coming to terms with the atrocity of its past while looking to the future to ensure equality for those in its community.

To best understand the Ocoee Massacre, it’s best to step back and examine the country’s treatment of the black communities — especially in the South.

In 1920 — only 55 years removed from the end of the Civil War — the so-called Reconstruction Amendments were in place toward the end and after the war.

Those three crucial amendments include the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery; the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States — including former slaves — and guaranteed all citizens “equal protection of the laws”; and the 15th Amendment, which states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

Although these rights were placed into the U.S. Constitution, there was a disconnect between written law and how it was carried out, said Pamela Schwartz, chief curator at the Orange County Regional History Center.

“While a lot of people were taught in their classes that emancipation means freedom, that’s not really the case,” Schwartz said. “We sort of set the stage moving up toward the 1920 presidential elections by talking about things like Black Laws and talking about things like Jim Crow laws, because what it meant was freedom was not really free.

“There were all of these other parameters that were put into place to oppress the black community, so the black community is walking out of enslavement with little,” she said. “They had no money, sometimes maybe not clothes and maybe not being literate even — so starting life anew. This is all sort of setting the stage for coming into early, early Ocoee.”

Following the Civil War, white veterans began to move into the Ocoee area, while a black community slowly was building between 1880 and 85. That’s when key figures from the night of the massacre, including Mose Norman, Valentine Hightower and July Perry, moved in from South Carolina to make a better life for themselves.

About 30 years before — around 1850 — James D. Starke moved to the Ocoee area with 23 enslaved black people and established citrus groves between what is now known as Starke Lake and Apopka. There, many black men and women worked.

During these early days, Ocoee saw its population rise to about 1,100 — although “Ocoee” referred to the general area and not the incorporated limits of the city — and the black community accounted for 45% of the population, wrote Lester Dabbs, former commissioner and mayor of Ocoee, in his master’s thesis, “A Report of the Circumstances and Events of the Race Riot on November 2, 1920, in Ocoee, Florida.”

And that community was divided into two sections. The first is known as the “Northern Quarters,” bound by Silver Star Road to the south, Bluford Avenue at the railroad tracks on the east (Fain’s Corner) and extending north toward Apopka and west toward Winter Garden. The second, known as the “Southern Quarters,” was the area bound by White Road on the north and extending in the other cardinal directions from that point, Dabbs wrote.

Between 1888 and 1920, members of the black community worked hard, saved money and bought property in a time of great prosperity and growth.

It was also during this time when the end of World War I and the Women’s Suffrage Movement helped create a sense of desire to become active citizens in the country.

“You had a lot of young black men go to war and the idea being that, ‘If we go and we serve our country, we’ve put our stake in and served this place — we should also have our voices heard,’” Schwartz said. “So coming home sort of instilled with this idea that, ‘We have our rights, and we should be treated equally and we should have our vote.’”

These two key moments led the push for a statewide voter registration drive in Florida. This push was led by prominent members looking to gain rights for the black community — which included Dr. W.S. Stevens. The leader of the Florida Knights of Pythias represented the Florida Voter Registration Movement in the Panhandle and helped members of the black community register to vote, said Paul Ortiz — a historian and professor of history at the University of Florida.

“There were all of these other parameters that were put into place to oppress the black community, so the black community is walking out of enslavement with little. They had no money, sometimes maybe not clothes and maybe not being literate even — so starting life anew. This is all sort of setting the stage for coming into early, early Ocoee.”

— Pamela Schwartz, chief curator at the Orange County Regional History Center.

“The reason that black Floridians were able to organize a statewide voter registration movement, the reason that people like Julius Perry and Mose Norman in Ocoee were able to get so many other black people to register to vote is this issue of trust — this issue of mutual aid, reciprocity of community,” Ortiz said during a recent virtual presentation on the 100th anniversary of the Ocoee Massacre. “On the eve of the 1920 election, approximately one out of every six black men in Florida were members of the Knights of Pythias.

“It wasn’t just a fraternal organization; it was your insurance policy,” he said. “You paid dues every month, if you died prematurely, your widow was paid what was called a death benefit. If you worked in the countryside and you were a sharecropper or you owned a small piece of land and your meal went down or took sick, if you were a fellow Pythias member, you were required to go help your brother or your sister.”

After World War I, when the group held its first state convention, the Pythias leadership gave members an ultimatum: Pay your poll taxes and you will register to vote — if not, you’d be expelled from the group. The organization also had a fund to help pay back poll taxes for working class and poorer members so they could vote in 1920.

Another vital group of the moment was the NAACP, when James Weldon Johnson saw the Great Migration as an opening of opportunities for black Southerners. So in 1916, he returned to Florida as field secretary of the NAACP and helped build the organization’s base in the state to help fuel voter registration.

Of all the groups pushing for voting rights, one of the most vital — and often forgotten — are black women, such as Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs leader Eartha M.M. White.

“Black women’s leadership is paramount,” Ortiz said. “Even before black women in Florida gained the right to vote with the 19th Amendment, black women — like Eartha M.M. White — are leading voter registration workshops right at the end of World War I. As their young men are coming home, people like Eartha White, Ms. Bethune … are signing up and making sure that men are paying their poll taxes and registering to vote.”

In Orange County, attorney W.R. O’Neal and Judge John Cheney — both Republicans — were trying to actively enfranchise members of the black community. In O’Neal’s case, the Republican was running for United States senator in 1920 and was looking for a boost in voting from those he was helping. In Dabbs’ thesis, he notes O’Neal and Cheney held secret meetings at a black church in the Northern Quarters to prepare black men to vote.

Word of these attempts to enfranchise spread and caught the attention of a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan — which, according to Dabbs, had its headquarters in Winter Garden; citizens in Ocoee and Orlando also held associate memberships.

In a letter dated Sept. 20, 1920, and sent directly to O’Neal, the white-supremacist group made clear their intent that what he and Cheney were doing to enfranchise the black community would not go without consequence.

“If you are familiar with the history of the days of reconstruction which followed in the wake of the Civil War, you will recall that the “Scallawags” of the north and the Republicans of the South proceeded very much the same as you are proceeding — to instill into the negro the idea of social equality,” the letter read. “You will also remember that these things forced the loyal citizens of the South to organize clans of determined men, who pledged themselves to maintain white supremacy and to safeguard our women and children.

“And now if you are a scholar, you know that history repeats itself, and that he who resorts to your kind of game is handling edged tools,” the letter continued. “We shall always enjoy WHITE SUPREMACY in this country, and he who interferes must face the consequences.”

At the bottom of the letter, the local Klan are informed by the writer to “Watch these two.”

Racial hostilities grew as Election Day approached, and the final sign of force from white supremacists came just two days before black men made their way to the polls. The Klan marched through Orlando and other areas of Florida in an act to intimidate black voters.

According to the Nov. 1 edition of the Orlando Evening Star, more than 500 Klansmen dressed in flowing white robes marched single file through the streets of Orlando that Saturday night. Although the number of marchers is debatable, the intent was clear, Schwartz said.

“The sentiment is essentially that they are trying to scare black voters from coming out to vote,” Schwartz said. “Again, this is evidence that the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacists were actively trying to suppress black voters at the time.”

The facts from Election Day 1920 are muddled at best, thanks in part to a variety of factors that include poor record-keeping, racially biased news reports and the decimation of a people.

What Schwartz and the Orange County Regional History Center found during their three years of research for their exhibit, “Yesterday, This was Home: The Ocoee Massacre of 1920,” were bits and pieces of a story but not the complete picture.

“One of the things that is the most dynamic and difficult about this event is that there are so many versions of this story — there is so much false memories, there’s conjectures, there is intentional obfuscations at the hands of white government officials to cover this event up,” Schwartz said. “So we, as a staff, took 129 accounts of what happened and synthesized them into one major account.”

Of those 129 sources, the history center only included the information that could be verified by primary source documentation or that every one of the accounts agreed on, Schwartz said. The end result was the following four paragraphs:

“On Nov. 2, 1920, Mose Norman, a black labor broker, attempted to exercise his legal right to vote in Ocoee, Florida. He was turned away and not allowed to cast his ballot. Later, a group of armed white men came to the home of Norman’s friend, July Perry, another black labor broker in Ocoee, and violence ensued. Shots rang out, and fires were started. Black residents were forced to flee from their homes.

“Badly injured by bullet wounds, July Perry was captured by some of the armed men and taken into custody. After receiving medical attention, he was left in a cell at the Orange County Jail in downtown Orlando. According to a State of Florida Coroner’s Inquest that took place on Nov. 3 and 4, 1920, an unidentified white mob overpowered the jailor, taking Perry from his cell. The lynch mob brutalized Perry, and by Nov. 3 had hanged his body in public view. His body was later moved to Greenwood Cemetery and buried. Mose Norman fled; he was eventually recorded living in New York City.

“Two men from the white mob were shot and killed, Leo Borgard and Elmer McDaniels, for which Carey Hand Undertaker’s Memoranda exist. Able-bodied ex-servicemen were called from across the region to come to Ocoee to create a perimeter to make sure the event did not continue, also blocking black residents from returning to their homes. An unknown number of black people were killed that night and others injured. Three unidentified black individuals were recorded as being buried in one grave in a Carey Hand Undertaker’s Memorandum.

“That night, many black residents fled Ocoee, never to return. Some stayed but were eventually driven out by the terror of that night as well as subsequent violence over the following years, including dynamite being thrown into their homes and individuals being beaten and threatened. After 1926, there would not be another recorded black person to reside or own for any length of time in Ocoee until at least the mid- to late-1970s.”

Based on an interview conducted by the Bureau of Investigation of William Blakely, a white man and inspector of elections, 114 ballots in Precinct 10 were cast in Ocoee that day. Those include ballots from 27 black individuals; July Perry and his wife were among those who voted.

From what is known, things went smoothly to start the day before the first challenge of a black voter — who Dabbs identified as Norman, though Schwartz wasn’t sure — at about 11 a.m. due to not having paid his poll tax.

Both Dabbs’ and Schwartz’s accounts said Norman had been placed on the stricken list due to failing to pay his poll tax; when Norman went to the polls in the afternoon, he was turned away. This is when the story begins to splinter, Schwartz said.

In Schwartz’s account, the white mob made its way to July Perry’s home in search of Norman at about 9 p.m. There, the first shots were fired. The violence continued; an unknown number of homes and buildings were burned, while black residents fled for their lives.

Dabbs’ thesis goes into lengthy detail of the events that followed Norman’s failed attempt at voting. In this account, Norman returned to his home, picked up a shotgun and returned to town. When he was stopped at Hoyle Pounds’ garage, a white man questioned Norman about his weapon — which he told the white man he used to hunt rabbits. When constable Bernie Cannon discovered the gun was loaded with buckshot, an exchange of vulgarities ensued, and Cannon disarmed Norman and struck him over the head with a revolver — Norman was then permitted to get in his car and leave, Dabbs wrote.

It was in the afternoon when Clyde Pounds, a deputy sheriff, deputized some 20 men to investigate the “trouble” at the Perry house, Dabbs wrote. However, another source found by Dabbs said it was Sheriff Frank Gordon who came out and legalized the group, while another source said it was just a group of men interested in “removing” Perry.

“Sam Salisbury led the group of men that went to arrest July Perry,” Dabbs wrote. “Upon answering the knock on his door, lantern in hand and seeing the white men assembled his yard (actually the house was surrounded), July said, ‘Yas suh, boss, let me git my coat.’

“As he turned to re-enter the house, Mr. Salisbury grabbed him and in the forthcoming struggle, pounded him on the head with the butt of an Enfield rifle as he held him by a neck hold with the other arm,” Dabbs continued. “Suddenly, a rifle barrel appeared from out of the house and was placed in the abdomen of Mr. Salisbury. Instinctively, the gun was brushed aside, and at that moment, the negro woman holding the rifle fired, the bullet striking Mr. Salisbury in the right forearm. This shot precipitated wholesale shooting by both whites and negroes there assembled.”

One account of this moment uncovered by Dabbs stated there were 37 armed black people in the Perry house — most of whom escaped through a trap door in the floor and fled into a cane field in the back of the house. It was then, during the shootout, when the two white men — McDaniel and Borgard — suffered their mortal wounds, while six others were injured.

Meanwhile, another account by a black man involved with the melee and a black woman who was a local school teacher in Winter Garden maintained that the only persons in the Perry house were Perry, his wife and his daughter.

“That night, many black residents fled Ocoee, never to return. Some stayed but were eventually driven out by the terror of that night as well as subsequent violence over the following years, including dynamite being thrown into their homes and individuals being beaten and threatened. After 1926, there would not be another recorded black person to reside or own for any length of time in Ocoee until at least the mid- to late-1970s.”

— Orlando Regional History Center

Dabbs’ thesis is fundamental to the understanding of the event by current Ocoee Commissioner George Oliver III — who was elected as the city’s first black commissioner in 2018. In Oliver’s eyes, the violence of that night was premeditated, and white mobs were looking for a reason to burn the black community to the ground.

“You have to understand the mentality of the mob at that point — especially from a law-enforcement perspective,” Oliver said. “Sam Salisbury is the chief of police in Orlando, who was deputized to raid this house looking for a fugitive from the law, so from their perspective, he has all rights to be there.

“He’s been deputized, ‘I’m already the chief of police, she shot me’ — an officer down in the line of duty,” he said. “So now to them, to that side, it’s a riot, because an officer of the law was shot while on duty. … So now, you have every excuse you need to do whatever you need to do to eradicate that entire community.”

Dabbs wrote the injured Perry was the last to leave his home, and he was wounded as he tried to escape into the cane field while his home and barn were set aflame.

Word of the violence spread quickly, and members of the Winter Garden and Orlando community began to arrive on the scene.

“News of the riot had been broadcast on a public screen in Orlando — a screen used to disseminate Election Day results — and literally hundreds of men flocked to the scene of action, armed to the teeth and espousing such epithets as, ‘Where are the goddamn niggers?’ or ‘I’ve come to kill a goddamn nigger,’” Dabbs wrote.

This mob of Winter Garden and Orlando residents was responsible for the burning of the Northern Quarters — the homes, churches and lodges all fell victim to the fury of the white mob, Dabbs wrote. The only building left untouched was the school building, which Dabbs noted was county property and therefore left alone. Meanwhile, the Southern Quarters also were left undamaged.

According to Dabbs’ thesis, after Perry was taken to the jail, he was removed by a white mob at 3 a.m. and hanged from an oak tree at the entrance of the Orlando Country Club. Accounts differ on other details that followed, but what is known is that the fires raged all night, and by the morning, the black community in Ocoee had changed dramatically.

It’s estimated there were about 280 people in the black community in Ocoee — 26 were landowners — before the events of Election Day 1920.

Land owned by black residents spanned over 368 acres and included 44 properties at the time of the massacre. Over the course of the next six years, the land and property owned by black individuals vanished. In the land-deed research conducted by Schwartz and the history center, the property owned by black residents in 1920 today would be valued at more than $9 million.

Although many believe the black community left the day following the massacre, in reality, that process took several years, Schwartz said. And many of those who fled had property in the surrounding area.

“The community did fight back, the community tried to stay and keep their property, but the violence was sort of ongoing … they were trying to push the black community out,” Schwartz said. “But by 1930, there are only two black individuals noted in the census in the community, and those are people who are servants in a white household.”

While property is a way to map the true decimation of a community, what haunts some folks such as Oliver is that the existence of the black community living in Ocoee at the time — which includes the three unknown black individuals killed that night — will be largely lost to time.

“There were several generations of folks that were wiped out or ran away and never told anybody else about it,” Oliver said. “There’s no birth records, because in 1920, African Americans, while they were doing very well … we were not very big on documenting who was born or how many children were born.

“You have to look at it from a perspective of, there are people who were born during that time — sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s — and lived in Ocoee who were either killed or ran out of Ocoee, and there are no records of them ever being there or being born there,” he said. “It’s almost as if they never existed. Can you imagine living on this earth and maybe putting in 10 or 20 years in one location and all of a sudden you’re killed or run off? You have no story, no footprint on this earth whatsoever.”

In the decades that followed, the city of Ocoee became a “sundown city.” The all-white community became a threatening place for black people to travel through, and it wasn’t until the 1970s when black individuals once again lived in the city.

Even when members of the black community began to return, there were still tensions. In a wall-length quote in the exhibit hall at the history center, Timothy James — whose family moved to Ocoee in the early 1980s — reflected on what it was like for his family.

“While we were living in Apopka, we were very comfortable, until we moved to Ocoee,” Jones said. “That transition was almost like sticking your finger in an electrical socket. I mean, we were really almost traumatized at the way people treated us just for being black.

“That was a wake-up call at the time where we thought we were being punished — and didn’t know why,” he said.

It was later in the decade — in 1989 — that a group of businessmen decided to form the West Orange Reconciliation Task Force. Its primary objective was to hold an annual event to commemorate the memory of what had taken place in 1920.

The hope was that this group would honor the memory of those black lives lost and heal a community haunted by its past. Instead, it did the opposite, said William “Bill” Maxwell, chair of the city’s Human Relations Diversity Board.

“A lot of dissension grew out around the fact of — and I’ve heard the statements made numerous times by local people — ‘Well, why do y’all keep bringing it up? Why don’t you just let it go and let it be and move on?’” Maxwell said. “And that’s a valid question for anyone who didn’t lose anything in the process of it.”

For years, the city avoided the 1920 massacre with the notion it had happened decades ago and there was no need to discuss it anymore. But thanks to the hard work by the West Orange Reconciliation Task Force, the city of Ocoee — via Resolution 2003-21 — gave birth to the HRDB Sept. 16, 2003.

The board comprises all volunteers and serves as a conduit to the city in relation to matters of racial equality and race relations.

As the years passed, nothing was being done to remember the massacre, but in January 2018, Maxwell wrote an update briefing and presented it to the commission with words that something needed to be done. The city was approaching the 100th anniversary of the massacre. In that timespan— from 1920 to 2018 — the city had 15 mayors come and go without any sort of action to remember the massacre.

“I explained to them, ‘We are coming into a season where all of those things that were done by your predecessors are going to come back to haunt you, so this is your wake-up call,’” Maxwell said. “I enumerated several things and sort of got looked at like, ‘Right, that’s exactly what we’re going to do.’”

As it turned out, 2018 would be a turning point for Ocoee as it related to the city’s acknowledgement of the massacre, as well as the first step of a diversified commission.

In March 2018 — decades after the black community had been pushed out — Oliver became the first black individual to win a seat on the Ocoee City Commission.

“When we put it into perspective, my win was more symbolic to most African Americans in Ocoee, and it would be considered to be redemptive,” Oliver said. “Now, almost 100 years later, there is someone that looks like them that is in a leadership position in the city.

“For me, when I ran, I wasn’t really focused on the fact that I was a black man — or being the first — that wasn’t really my aim at all, that just happened to be a caveat,” he said. “For me, the focus was on the citizens of Ocoee — the focus was the city deserving better and moving the city forward.”

A year later, in 2019, Oliver would be joined on the commission by Larry Brinson — a retired U.S. Marine who served his country for more than 20 years. So now, almost 100 years later, two black men occupy seats in the highest form of government in the city.

In April 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice — which memorializes the more than 4,400 black men, women and children who were victims of racial violence — opened in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Selma-born Maxwell decided he was going to go. After getting approval from the city, Maxwell traveled with a small group — which included current Ocoee Mayor Rusty Johnson — to Montgomery to take in the museum and the events taking place.

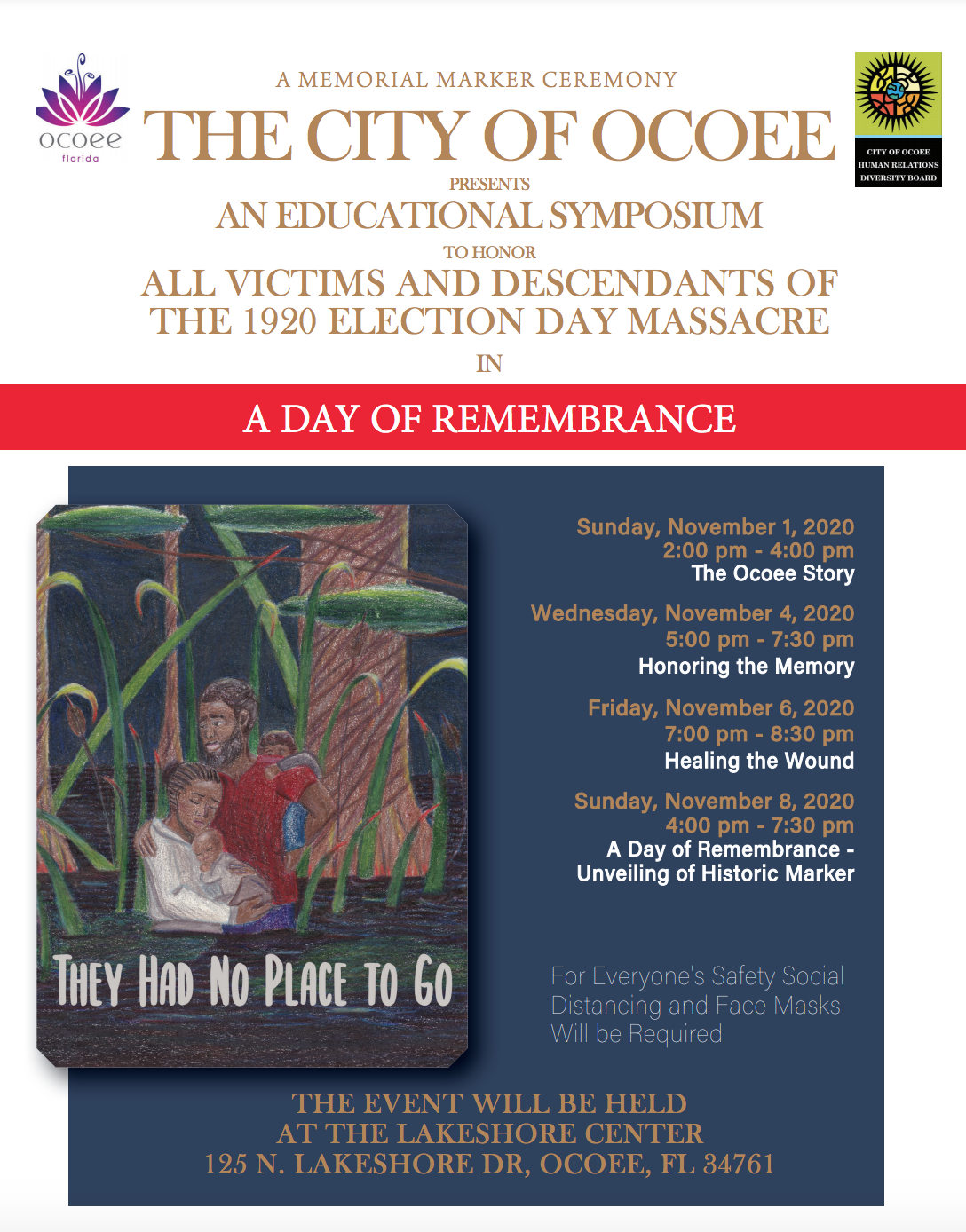

By the end of the trip, each member walked away with a new perspective, and it was then when Johnson told them to begin plotting out ideas for what could be done. What the HRDB came back with was an agenda that would dedicate the first week of November — from Sunday, Nov. 1, to Sunday, Nov. 8, 2020 — to putting on programs and events to honor those lost in the massacre while educating the public.

As part of the events, an official apology will be read, while the final day will conclude with the unveiling of a new historic marker dedicated to the victims of the 1920 massacre. The idea for the marker was a part of a proclamation read by Maxwell at the City Commission meeting in November 2018 — a proclamation that read in part, Let it be known that Ocoee shall no longer be the sundown city but the sunrise city, with the bright light of harmony, justice and prosperity shining upon all of our citizens.

“Ocoee is a great city with a great quality of life,” Johnson said in a written statement. “We have made huge strides to overcome a reputation marked by events that happened here in 1920. We have advanced way beyond those times and have put tremendous effort into overcoming our past.

“I have personally been blessed to take part in helping bring awareness and reconciliation to this city,” he continued. “The remembrance events planned the first week of November will recognize the city’s past. But we must also recognize how far we have come after much hard work by members of our community, the City Commission and especially our Human Relations Diversity Board.”

Although the violence and destruction that took place against the black community in 1920 cannot be undone by any means, the city coming to grips with its past is the necessary first step to a better future, Oliver said.

Although many, including Maxwell, believe the city should have acted sooner, what is being offered now is something that Maxwell has fought so hard for since he first moved to Ocoee years ago. This is a moment that could — and should — be a means of finally finding some sort of peace.

“It’s a terrible thing that happened — there are no words that can be uttered that would offer any form of justification, but we couldn’t stand still in 1920 and hope for today, lest we still be having those type of riots,” Maxwell said. “As unfortunate as it is that lives were lost, time — the continuum of time — has continued to move us forward.

“Only we in our inabilities to absorb the essence of what took place linger in the past,” he said. “Time marches on, and on marches time.”